This is Part 4 of a series. Be sure to check out Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3!

The secret to world peace is not as complicated as we make it out to be. Quite simply, the world would be a much better place if we all traded our cars for scooters. And by scooter I don’t mean motorcycle. If your knees can’t touch, you’re not on a scooter.

The mechanism of peace through scooters is twofold, even before getting into the macro-economic and geopolitical implications of a billion people dramatically reducing their carbon footprint. It’s simpler than that.

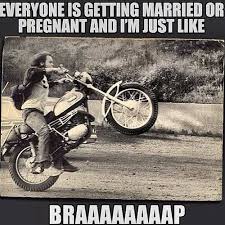

- It’s pretty much impossible to be in a bad mood on a scooter. And when you’re in a good mood, you’re more likely to be nice to people. And when you’re nice to people it puts them in a better mood. So on, and so forth, until everyone goes home a little bit happier and we can stop reading about stuff like this, and more stories like this.

2. Exposure to danger induces behavior that looks like empathy (if not empathy itself). Everyone should have a little skin in the game.

And that’s it.

There are basically two arguments for driving a large car, SUV, or truck. On the one hand, you’ve got the increased safety provided by the larger vehicle, and then the honest people who are just like, “WOOOOOOOOOOO!” That second group can be hard to reason with.

But the first group tends to be reasonably well meaning. They’re interested in safety for themselves and their loved ones, after all, which is hard to fault. Never mind that SUVs aren’t actually all that much safer than passenger cars. The taller, heavier vehicles are much more prone to rollover accidents, which carry a high rate of fatality.

In fact, the main case for claiming that an SUV is safer than a Honda Fit, or better yet, a Honda Ruckus, comes from frontal crash test ratings. If we remember from high school physics class that momentum is conserved, it should be no surprise that the larger, heavier vehicle fares better in a head on collision.

But that’s also a pretty fucked up way to approach safety.

By driving a Ford Expedition in the name of safety, I am saying that my well being is more important than your well being. That I am more important than you are. The only way a truck makes you safer is at the expense of another person. That kind of narcissistic decision making trickles down to our behavior, as well. I’m much more likely to drive aggressively or flip you off from the confines of a rolling, 5,500 lb. safety cage.

Taking us all from our cars and placing us in the relative danger of a 49cc fun machine will not make anyone more empathetic. Sure, humans can learn to be empathetic, but let’s be real: that sounds like a lot of work. Instead, exposure to risk induces behavior that appears empathetic.

You’ll be much less likely to drive like a dickhead if rather than simply saying “I’m sorry” and getting some body work done (because apparently in the US you can avoid the consequences of killing a fellow human with your car with the proper application of puppy eyes and a heartfelt apology), you’re confronted with leaving most of your skin on the pavement in a crash.

The problem with driving is that we don’t think twice about doing it. It’s one of the most dangerous things that we all do, but we hop in, turn up the music, and start scrolling through Instagram. If every time we had to drive somewhere we were a bit more afraid that we wouldn’t make it, we’d pay a lot more attention on our way across town, and we’d be in a better mood when we got there.

Like