When we got out of the car near the ponds it was still dark except for a faint grey that backlit the jagged black horizon of the Mission Mountains. Our breath clouded in front of our faces and our boots broke through the ice that formed overnight in the rutted road. It was almost ten years ago now that my friend Ben and I crunched through the ice and frozen grass with shotguns and a thermos of coffee and he took me out duck hunting for the first time.

A few hours after we left the car the sun was up and we’d sweated through our warm clothes. We found ourselves cradling small porcelain cups of threadbare drip coffee in Connie’s Countryside Cafe, across the highway and down the road from where we hadn’t shot any ducks. “You gotta let ‘em get way closer,” Ben told me. “You can’t shoot a duck from 200 yards.”

I’m not a great hunter. I grew up in a place where the word “gun” invoked news clips of gang violence rather than crisp October dawns and the whine of an elk bugle. Meat came from the grocery store on a styrofoam tray. When I eventually bought a rifle my aunt asked my if I had turned into a Republican and she was serious.

But in Montana I was drawn to it. I liked the ethic of healthy, sustainable harvest. Of being a part of the ecosystem, rather than just watching it on tv. I kept my college roommate, a lifetime hunter, awake for countless nights with questions about the difference between a mule deer and a whitetail, a license and a tag, and what kind of gun I should get to learn how to hunt. I found an affordable rifle, and later an affordable shotgun. I embraced the challenge with early mornings, long days, and no clue what I was doing.

It turns out hunting public land in Montana is pretty hard. In ten years I’ve shot two deer, three grouse, and really scared about a half-dozen ducks, but I know skilled hunters who have filled their freezers with more than that in a day. Eventually I stopped saying that I was going hunting, and started saying that I was going for a “rifle hike,” but the ceremony of it kept me coming back. It was an opportunity to get up early, and to see a part of the world I wouldn’t otherwise. To move deliberately and be alone for a while.

But like anything, passions evolve and interests change. My enthusiasm for the sport has ebbed and flowed over the years. After a few seasons I started racing. Racing bikes took the limelight from rock climbing in the summers, ice climbing in the winter, and chasing ungulates through a haze of confusion all fall.

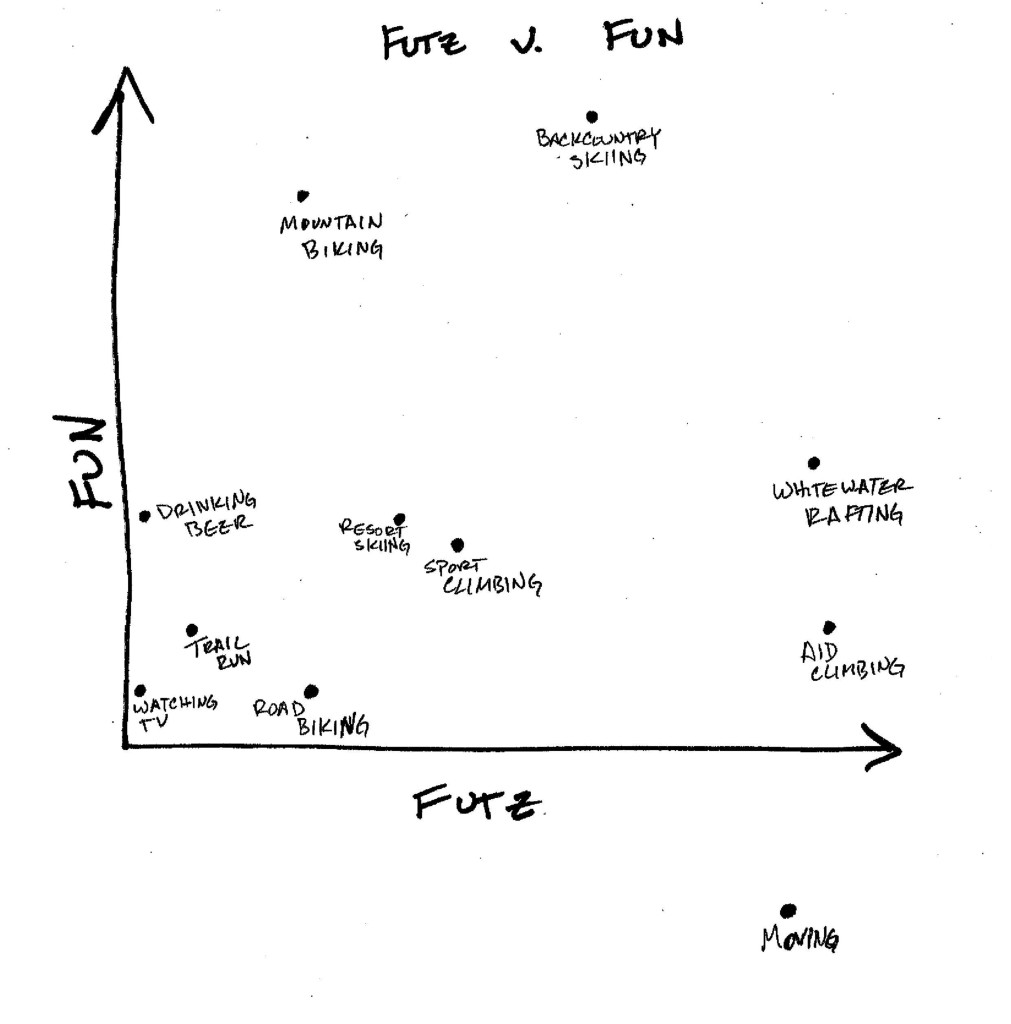

With racing came training. Training is a word for when you take something fun, that you enjoy, and make it into something unfun, a chore that hangs over the evening somewhere between work and dinner, and has a way of occupying most of your life if you’re not careful.

A friend from out of town asked me, the local, for a place to go for a hike. He wanted to know where I go when I hike. It dawned on me then that I don’t hike. I go for trail runs. I ride my bike in the backcountry. If I do hike, it’s a kind of aerobic training experience where I still wear running shorts and don’t bring enough water and end up really tired.

I haven’t raced seriously in a couple of years now, but I’ve still let the idea of training govern how I spend my leisure. I still go for trail runs instead of hikes, and find myself riding my bike at lactic threshold for no good reason at all. I like the sensation of discomfort and training, but I also miss the calm of a more patient sport. I simply lack the willpower or the attention to slow down and breathe.

And I think that’s why I feel myself being drawn back to hunting. It forces you to slow down. When you’re a crappy hunter every day of hunting is really just a hike.

Like