“He was the single most hopeful man I ever met, and I’m ever likely to meet again.” – Nick Carroway, The Great Gatsby

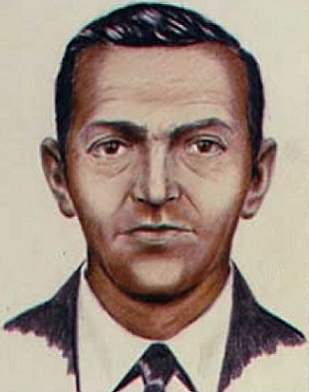

On the eve of Thanksgiving in 1971 a man bought a ticket aboard a Boeing 727-100 for a quick flight from Portland to Seattle. Once the flight was underway, and from a seat near the middle of the plane, he handed a flight attendant a note describing a bomb in his carry-on. He showed her a tangle of wires to demonstrate the seriousness of his claim. If he did not receive a ransom of two hundred thousand dollars and a selection of parachutes, he would detonate his bag in mid-flight.

We’ll never know if the man who went by Dan Cooper really had a bomb. Hours after the hijacking began he was bound for Mexico with a bag filled with cash and a parachute. Somewhere over Oregon he opened the Boeing’s rear hatch to jump into the freezing November rain and illuminate the imagination of generations. He was never seen or heard from again.

A few weeks ago the FBI officially closed the case: unsolved. At some point they had to get tired of fielding deathbed confessionals from people who claimed to be D.B. Cooper or the Lindbergh Baby but can’t be sure which one. But there’s still something captivating about our nation’s only unsolved airplane hijacking. There’s an infectious kind of hopefulness in carrying off a plan like that.

I can hear your incredulity now. A hijacking, you say, is the most violent throe of desperation. But hope and desperation are on equal footing in the foundation of the American Dream. We are a nation built by refugees who fled untold horrors for a crack at a new life. In fact it’s only a deeply rooted tradition of hope that can explain the rise of D.B. Cooper as a legend. Who can really believe that an untrained man could jump alone above a rugged wilderness and into a freezing storm at hundreds of miles an hour in the middle of the night wearing only a polyester suit and survive?

It’s this hope that drew settlers to a New World, then to the farthest flung corners of it in search of gold. Hope has a way of gnawing at us, and like gold itself it’s as much a gift as a curse. It allows us to believe that the future will be different from the present, not through a commitment to self-improvement, but through the work of chance. And even to this day nothing captivates us like the prospect of hidden gold.

Buried treasure is the stuff of high adventure. Of the movies and books that guided our understanding of what it means to go on an expedition. From the mutiny on the Hispaniola to the riches of the Sierra Madre to a ramshackle group of kids on the Oregon Coast, a search for hidden treasure has provided a simple and tangible objective to catalyze adventure.

But in our Brave New World the hope of improbable prosperity has been watered down to gas station keno machines and scratch-off lotto tickets. There is no buried treasure. Or is there?

Forrest Fenn’s goal was to leave a legacy behind. The millionaire art collector was battling cancer and planned to die alone in the woods, leaving a bronze chest of gold clutched in the hands of a skeleton for a future adventurer to find. Well, he beat the cancer but still thought the treasure chest was a neat idea, so he hid one somewhere in the Rocky Mountain west. No X marks the spot, but a poem gives the clues.

Forrest Fenn’s claim to have hidden a great wealth of treasure somewhere in the mountain west is outlandish. It’s improbable. The cynic in me calls it a ploy to sell copies of his book. But then there’s the hope. Not so much the hope that I find the hidden gold, but the hope that someone of means so believed in hope itself that he really did hide a collection of gems and doubloons.

Because the gold isn’t really the treasure. It’s the idea that the gold might be out there, sitting in a hole or a hollow tree, just waiting to capture the imagination of a new generation of adventurers.

And if we never find it? Well, as long as we look, that might even be the point.

Like